On Monuments

These pieces concern the seemingly intractable problem of monuments to the Confederacy on Monument Avenue in Richmond, VA. It is worth noting that the work published here was developed between 2016-2018. Since then many changes have taken place as a result of the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing protests. Protests in Richmond centered on the monuments on Monument Avenue — all of the monuments to the Confederacy were removed in 2021. The work presented here was installed as part of a two person show at Mary Baldwin College in 2018. This exhibition was met with resistance from a group of students and some faculty members. The truth about the possible interpretations and meanings present in the work is admittedly complex, however the Mary Baldwin administration asked us to take the exhibition down. Afterwards, through holding discussion sessions which excluded us, effectively silenced us. The following is a quote from a school representative: “If I felt the environment were conducive to positive learning moments as we move ahead the next few weeks I would resist the idea of removing the work; however, our climate is moving in a direction that precludes reception and processing of this provocative and complex work in a direction I had hoped for originally. For this reason, if you and Jere decide to remove the exhibition I will support your decision.” There is a great deal to say about the nature of academic integrity, freedom of expression, upholding good civil discourse and abiding by a diversity statement that is quite ironic in this light, but that will for now remain unsaid here.

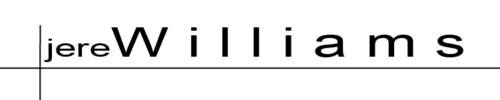

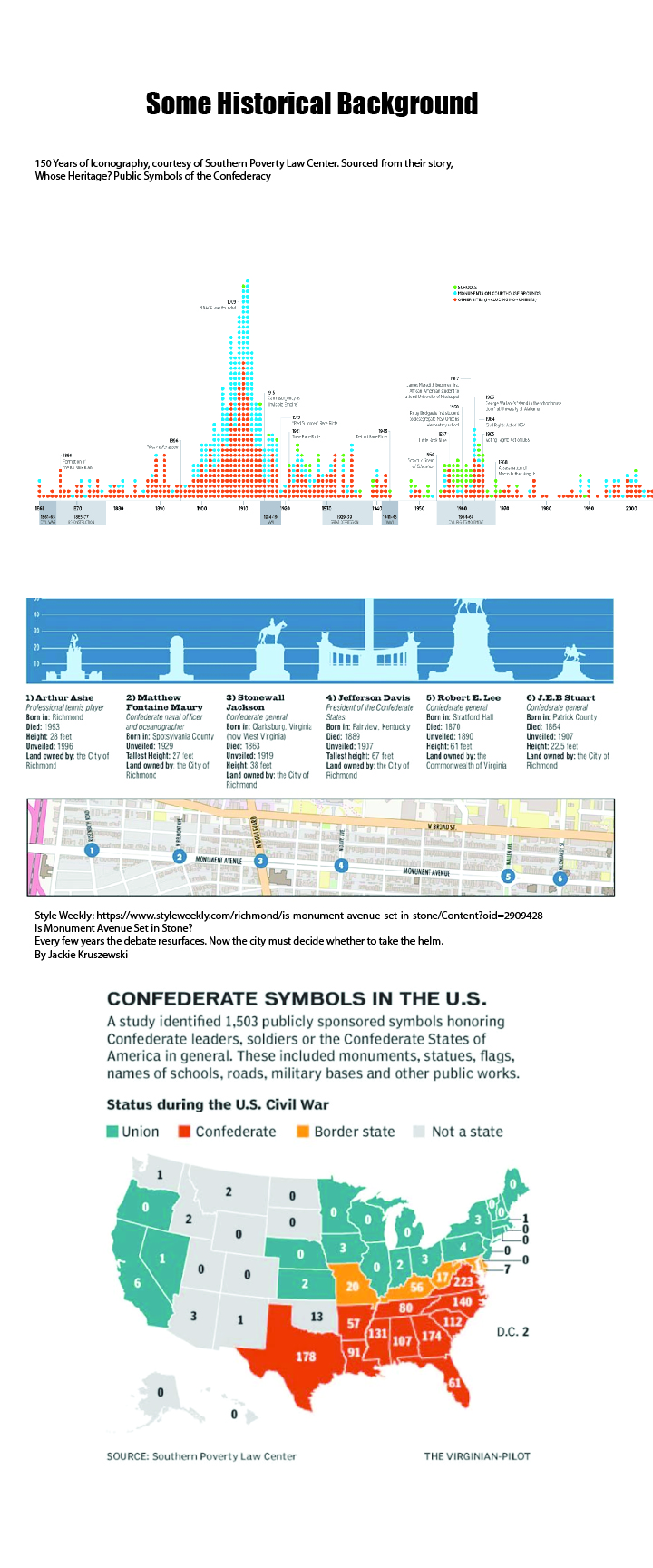

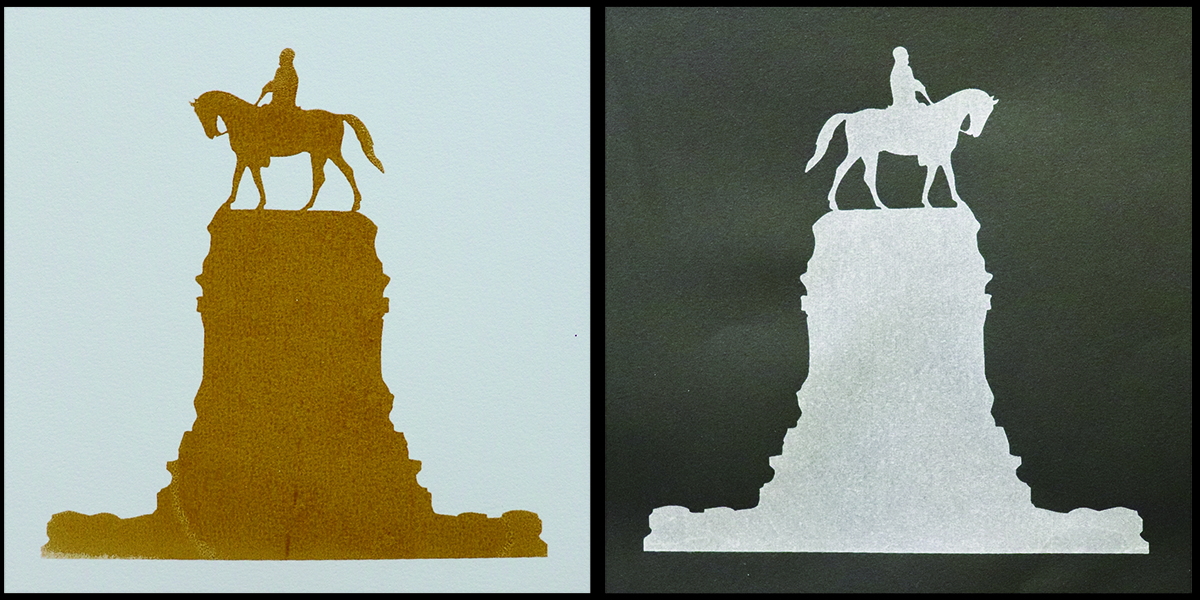

In this image gallery are some of the individual works that I installed in the show: two digital pieces, two screen prints (in sour cream and molasses), one painting in tobacco juice, one sculpture of a sink with Stonewall Jackson air fresheners with “Christianity” printed on them, and two collaborations of cut-up monument screen prints. The first image here is a factual infographic from various sources about the monuments and Confederate symbols in Virginia. This infographic was installed in the corner of the gallery with the sound work I created. In this sound piece I asked roughly a dozen diverse (in race, age, and gender) people what they would do with regard to the monuments on Monument Avenue. The resulting work featured a continuous loop of my voice asking the question followed by all the answers playing simultaneously. Imagine this sound piece; everyone has an opinion they want to express and it is impossible to follow one person’s answer. The result is, metaphorically at least, that we don’t hear each other. If it’s difficult to read, the digital piece with Robert E. Lee has the expression “nothing is inevitable” written on (digitally imposed on) the yield sign. The result of the protests has resolved the force of this ambiguous expression such that there is now nothing on the land in the middle of the traffic circle. At this time I do not know what the plan is for the space. The Jefferson Davis piece has the expression “I’m a good Christian” on the digitally constructed sign. Christianity has been used over the past thousand years or so as a background rationale for actions that seem obviously in contradiction to its tenents, and this issue is no exception. It doesn’t follow from this that Christianity should be abandoned or is inherently bad but it does follow that there is a need to closely examine the exegesis one adheres to (and to honestly address any contradictions).

My intention was ultimately to work towards understanding/awareness if not a solution to what I perceive to be the problems posed, to all of society, by the presence of these monuments in public space (they exist without even a single word of contextual commentary to accompany them). The work is not an expression of what to do with the monuments, but rather it identifies a significant cultural problem while acknowledging the fact that these monuments are present in Richmond as installed -beginning in 1890. The double entendre “nothing is inevitable” is a good example of how different interpretations of the same thing can be so polar opposite. There were other works in the show and mistakes were made, however, it was proven true that the real problem (and the intellectual content of my contributions to this show) is at root an inability to have meaningful civil discourse. There is a great deal to discuss on this topic and the need for real civil discourse is significant here.

OUR ORIGINAL STATEMENT published with the show

STATEMENT FOR RELEVANT / SCRAP

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, roughly 1,500 place names or symbols representing the Confederacy can be found in public spaces in Virginia alone. Of that number, over 200 are located in public spaces maintained by local or state government. Monuments to the Confederacy have grown particularly controversial in recent years, and we can no longer ignore their significance regardless of our political views.

The work in this exhibition expresses our consideration of the complexity of the situation, and the current post-truth context in the U.S. seems to be adding to that complexity. The inability to agree on basic facts, such as why the civil war was fought, across the argumentative divide results in a situation where all voices, all viewpoints are simply sounding-off simultaneously. It is this cacophony of individual postures that some of the work in this show illustrates. We are all stakeholders in what happens with regard to monuments to the Confederacy, and it is clear that the status quo is not enough to prevent further civil discord. We must come to an agreement, collectively, on how to proceed.

We both grew up in the South (Virginia and Georgia) and have observed our own changing relationships to monuments to the Confederacy. Being white in the South meant for us that these monuments could be treated like furniture in the environment, relegated to the background through habituation and affiliation. In other words, we were privileged not to see them as contesting our rights or place in society. As we grew up it became clear that these public monuments did not represent the values of everyone. This is a fairly typical story for many of us. The issue does get complicated as we begin to assess the various arguments on both sides of the controversy. The clash is pronounced when considering the preservation of history, the commemoration of war dead on one side and social justice on the other.

“Are Confederate monuments reminders of the antebellum South, a mythical place where tradition, family, chivalry, a love of liberty, and a small government were paramount virtues, or do they recall an odious, divisive time in the nation’s history where bigotry, slavery, and rebelliousness where championed?” (Confederate Symbols in the Contemporary South. Edited by Martinez, Richardson, McNinch-Su, p. 173)

Consider this thought experiment (that actually happened). You are the director of the Civil War Museum and the Sons of Confederate Veterans approaches you with an offer. They want to donate to the museum a bronze sculpture of Jefferson Davis walking, holding hands with two young boys (one black and one white). They have picked out a location on your campus, and they are ready to install. How do you respond to the Sons of Confederate Veterans?

Jere Williams and Pam Sutherland